Seton Initiative Aims to Boost Enrollment, Raise Achievement at Catholic Voucher Schools

Seton Catholic Schools, a WCRIS partner, was featured in the Milwaukee Journal on Saturday. Read below about how they are changing what private education looks like in Wisconsin and how their model is gaining national attention.

The article:

In the not-too-distant past, teachers at St. Catherine Catholic School in Milwaukee ran their classrooms much as they had for decades. Most days you’d find teachers lecturing from the front of the class to students — sometimes bored and glassy-eyed — in neat rows of desks.

These days, students at St. Catherine often work in small groups, with teachers moving from pod to pod to offer individualized instruction based on the students’ needs.

It was a big shift for St. Catherine, but students have responded well, according to Principal Mike Turner, who said the old-school model of “teaching to the middle” only worked for a small group of kids.

“They like it a lot. They’re very excited when they’re able to work together, to problem solve, create a project and demonstrate their learning,” he said.

“And it’s improving their social skills … because they’re learning to work cooperatively with one another.”

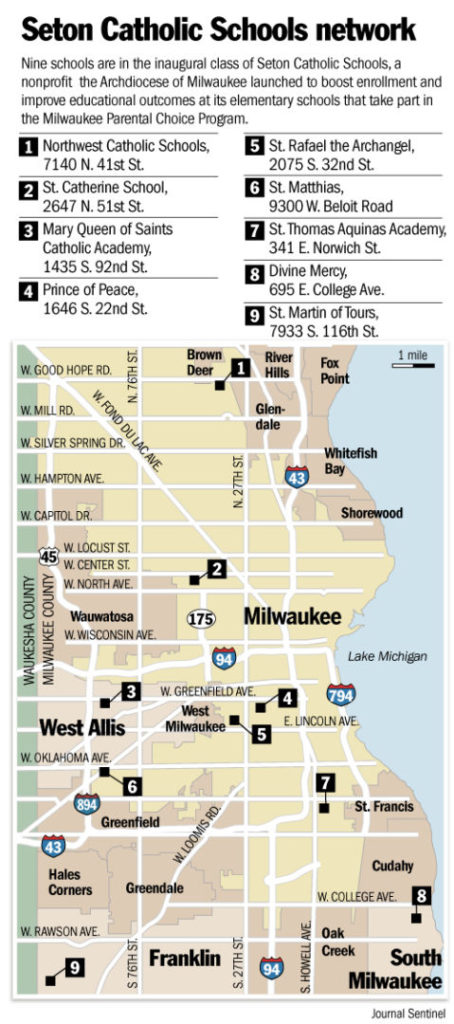

Turner is in his second year at St. Catherine, one of nine schools in the inaugural class of Seton Catholic Schools, a nonprofit the Archdiocese of Milwaukee launched to boost enrollment and improve educational outcomes at its elementary schools that take part in the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program, which offers taxpayer-funded vouchers for low- and middle-income students to attend private schools.

Adopting more innovative teaching practices is just one of many priorities Turner has set for St. Catherine — up there with raising test scores, expanding extracurricular activities, and creating a culture where students and families feel welcome.

“I have a lot of ‘number one priorities,’ ” said Turner, who spent 15 years as a Milwaukee Public Schools teacher before joining St. Catherine in July 2015. “We’re a work in progress. But we’re making progress.”

The nonprofit Seton network, which will eventually include 26 urban and inner-ring suburban schools, is one of a number of initiatives around the country aimed at reinvigorating Catholic education in urban communities. They come as an increasing number of states are offering private school vouchers, and as a new emphasis on transparency and accountability — at least in Wisconsin — is putting pressure on all schools to improve the academic outcomes of their students.

“We believe that education is fundamental to health, to the success and happiness of people and to a strong community,” said Don Drees, a former management consultant who is leading the initiative as president.

Seton’s $3 million budget has been financed largely by $2 million in gifts from the Faith in Our Future Trust, created by the archdiocese in 2007 to hold the proceeds of a $100 million capital campaign to bolster Catholic education.

Seton has hired more than a dozen employees, many well-known in the Catholic and public school and school reform arenas, including former Greendale Superintendent Bill Hughes as chief academic officer.

And it’s now laying the groundwork for a $25 million capital campaign.

“There’s a lot of work to be done. All of our students have great strengths, but they also have a lot of challenges,” said Hughes, a school choice advocate who worked most recently at the reform nonprofit Schools That Can. “And we have a lot to learn.”

The first nine schools serve about 2,090 students, almost three-fourths of whom attend on taxpayer funded vouchers. A second cohort of five schools is expected to be added in January.

This year’s schools range in size from tiny St. Martin of Tours in Franklin, with about 88 students, to Prince of Peace on S. 25th St., which enrolled 461 students this year. Two schools — St. Catherine and Northwest Catholic — serve mostly African-American students. Overall, about half of the students are Latino, and 30% are white.

Abject or growing poverty presents challenges at most, if not all, of the schools. At four, including St. Catherine, 90% or more of the students are considered economically disadvantaged.

“Mr. Turner, do you have any pants?” one boy asked, pointing to his ripped knees, as Turner made his morning rounds one day this month.

“I do,” he answered. “We’ll get those today.”

“We’re not naïve to the challenges our families face,” said Turner, whose school receives donations of gently used uniforms from the nonprofit St. Vincent de Paul and others.

At Divine Mercy, in South Milwaukee, which also joined Seton this year, about 20% of the students are eligible for free-and-reduced lunch, said Principal Liz Dworak.

“Our population is not rich by any means,” she said. “I had a father in just the other day who was near tears because he … couldn’t buy his daughter’s winter boots. We have a generous family who was able to take care of it for them, no questions asked.”

Jump start for schools

St. Catherine and Divine Mercy are, in some ways, very different schools. But both were struggling with declining enrollment and on the verge of closing in recent years. Instruction lacked zest and rigor. At St. Catherine, test scores were falling, including for white students, who typically outscore other racial and ethnic subgroups of children.

Both principals jumped at the chance to join Seton’s first cohort of schools.

“I lobbied — very hard,” said Dworak, whose school began accepting students through the Milwaukee Parental Choice voucher program in the fall of 2012, just to keep the doors open. “There’s so much potential at this school. It just didn’t have the resources to make it happen,” she said.

As part of Seton, the schools retain their own parish identities and cultures, but Seton has assumed and consolidated many of the back-office functions — purchasing, hiring, professional development — that are often time-consuming and more costly for individual schools.

It boosted salaries and just announced it would offer a new retirement annuity in an effort to attract and retain talented staff. And schools got some “lipstick projects” — fresh paint and newly waxed floors at Divine Mercy, for example; a new playground and bright yellow awnings at St. Catherine.

It has updated curriculum, added coaching for principals and teachers and instituted other practices — individualized learning and an emphasis on student performance data, for example — favored by higher performing public and charter schools.

“I’ve watched the teachers go from being these little islands to being really collaborative in their work,” Dworak said. And the kids, because we share a lot of our data with them, they’re really interested in how they’re doing.”

There’s a renewed emphasis on reading and math, on data collection and analysis, and on accountability for student achievement based on test scores.

One of the first decisions Seton made was to require all students — not just those on vouchers — to take the Forward Exam, the state’s annual achievement test, to set a base line for improvement, Hughes said.

He declined to share the individual schools’ scores. (The state publishes only voucher students’ scores.) But he said they will eventually be posted on schools’ websites so parents can make informed decisions about where to send their children.

“I believe in three to five years, we’ll be more competitive, and that will drive our enrollment and success,” he said.

Hughes said the schools also will “break some of the old molds,” such as selectively enrolling students and limiting numbers of students with special needs.

Decline in Catholic schools

Catholic school enrollments peaked in the 1960s, when more than 15 million students were educated in 13,000 schools across the country, staffed primarily by religious sisters who offered a plentiful source of low-cost labor, according to the National Catholic Education Association. The movement of sisters into other ministries dramatically altered the economic picture for Catholic schools. And enrollments declined over the decades driven by a host of reasons, including rising tuition costs and a lessening of the moral obligation for Catholics to send their children to religious schools.

By 2015-16, there were just 6,525 Catholic schools, serving about 1.9 million students nationally. Enrollment in the Milwaukee Archdiocese is 30,772 this year, down from 33,559 in 2007-08, according to Kathleen Cepelka, who serves as superintendent for its 92 elementary and 15 high schools across the 10-county area.

The genesis of Seton goes back decades, Cepelka said. But it built steam in recent years with the creation of the Faith in our Future Fund and the recommendations of the archdiocese’s 2014 synod, which urged the local church to take a greater interest in the issues of urban Milwaukee and to free its parish priests of some of their administrative duties, including oversight of schools.

The shift in the schools has been an adjustment for many. Some teachers left rather than adapt to the new expectations, and some were asked to leave.

“It’s not to say that these weren’t good people, or not dedicated. But they weren’t fully on board. And they may not have been able to meet the demands of what it means to really raise standards,” Cepelka said.

It was a welcome change for Michelle Lewis, dean of students and fifth-through-eighth-grade teacher at St. Catherine.

“It’s a lot of new ideas, very innovative, a better curriculum,” said Lewis, who taught at Greater Holy Temple Christian Academy before joining St. Catherine four years ago.

The school climate is different, she says — quieter and more serious, kids aren’t wandering the halls, and there’s more homework.

At Divine Mercy, Dworak said, teachers have for the most part “really embraced the changes.”

“The biggest change is that teachers are excited about teaching again, and the kids are excited about learning,” she said.

“Seton has given us hope,” said Dworak as she walked through the halls of the South Milwaukee school.

“Five years ago, they were talking about closing … and now new life has been breathed into this school,” she said.

“For people who have been in Catholic education for a long time, this is really exciting.”